7-Minute Read

I recently attended a conference where the presenter’s first slide was titled, “8 seconds.” The audience had to guess what that meant. Someone shouted out “bull riding”, which was funny seeing that we were in Texas. To our surprise, however, it meant that 8 seconds was the average attention span of a human being today. In the last two decades, it has declined by about 40 percent. This is humbling considering that the attention span of a goldfish is 9 seconds.

The problem is that our ability to pay attention, one of our most precious qualities as humans, is gradually withering away. As author and journalist Yohann Hari describes in his book Stolen Focus, there are many reasons for this. Some are more obvious, such as the impact of social media and stress, while others, like pollution, could come as a shock.

Solving this problem is not easy. There are issues that must be addressed at a societal level if we are to fix this at its root. However, it made me reflect on all the efforts I make to tackle this individually, and I thought it would be worth sharing.

Every aspect of your life is connected to your attention, including your financial well-being. Imagine a life where you can focus more deeply on the (presumably fewer) things that truly matter to you. It sounds idealistic, but it’s a valuable quality to cultivate. Perhaps it could even lead to a life with reduced anxiety. Do you think that if you had greater focus and less anxiety, you could make better financial decisions?

And with that, I thought I’d share some of the best tips I’ve come across in the fields of technology use and time management. Most of these I apply regularly myself, but almost everything has room for improvement, and it requires diligence to avoid regressing.

Before getting into the tips, I should mention that I write this from a certain level of privilege. As an independent small business owner, I enjoy a degree of autonomy and time freedom that not everyone has. Your family, financial, and professional obligations may present challenges to implementing these tips. As you read this, consider what resonates with you or what you might even disagree with. Reclaiming your attention is an ongoing battle, but one worth fighting.

Limit Your Technology Use

Turning off your phone notifications is a huge step in the process of refocusing yourself. The alternative is being in a state of constant interruption from spam calls, texts, and the array of potential app notifications.

It’s pretty easy to turn off notifications, yet I’m often surprised by how many people don’t. If you’re in a focused state of work, one distraction can take you twenty minutes to get back to the same state. This has sadly become sort of the new normal.

Of course, you want to be reachable during real emergencies, such as a family member needing to contact you. You can override your notification settings for specific people or circumstances. On top of this, you can set your phones to different modes, such as work or sleep, and have them run on an automatic schedule.

However, if possible, when you’re trying to focus on work that requires concentration, leave your phone in a different room altogether.

Next, implement an office hour strategy for your email. This means you allocate specific times during the day to check and respond to emails. You shouldn’t be constantly immersed in your inbox, nor should you treat your email as a to-do list. Like phone interruptions, switching between emails can be harmful due to the cognitive costs associated with shifting between different mental states.

Consult any productivity expert, and they will advise you to use a different system to track your tasks, projects, and appointments. It doesn’t have to be a complex system. While we probably can’t avoid email, there are many hacks and tips available for managing it. Some even advocate for getting your inbox to zero. There’s an aesthetic to that, but I don’t think it’s necessary.

I believe that building your focus muscles requires spending as much time away from email as possible. In my profession, this is a delicate balance because email is one of the primary ways I receive updates or questions from clients. I’m mindful of being responsive, but I’m grateful that my clients don’t expect immediate responses. I believe it ultimately serves them better when I can spend my time thinking through more challenging problems.

Finally, consider quitting social media. While this can be an extreme shift, we must seriously assess the negative effects it has on the quantity and quality of our attention. I’ll clarify that I don’t literally mean quitting ALL social media. The main culprits are those that use algorithmically curated content to keep you doom-scrolling. There are ways of using social media for productive connections, but it’s a slippery slope.

The engineers behind the development of the primary apps used today employ every psychological trick in the book to capture and retain your attention. The business models of these companies necessitate that they are designed this way. As they emphasize in the documentary, The Social Dilemma: “If you’re not paying for the product, then you are the product.”

Hari pointed out something that struck me. It would be easy for programmers at these companies to build a feature that lets us see when a friend is nearby and encourages them to meet in person. However, that hasn’t happened because it risks losing their attention and advertising dollars. Until the economic and incentive structures change, we must remain diligent.

I know that it will take more than a few words in a blog post to get you to limit social media or quit it altogether. I think a more practical approach could be to do a “30-day digital declutter.” Cal Newport proposed this idea in his book Digital Minimalism. There are three “simple” steps:

- Remove any distracting technologies in your life for one month.

- Use your newfound free time to pursue “high-quality leisure time.”

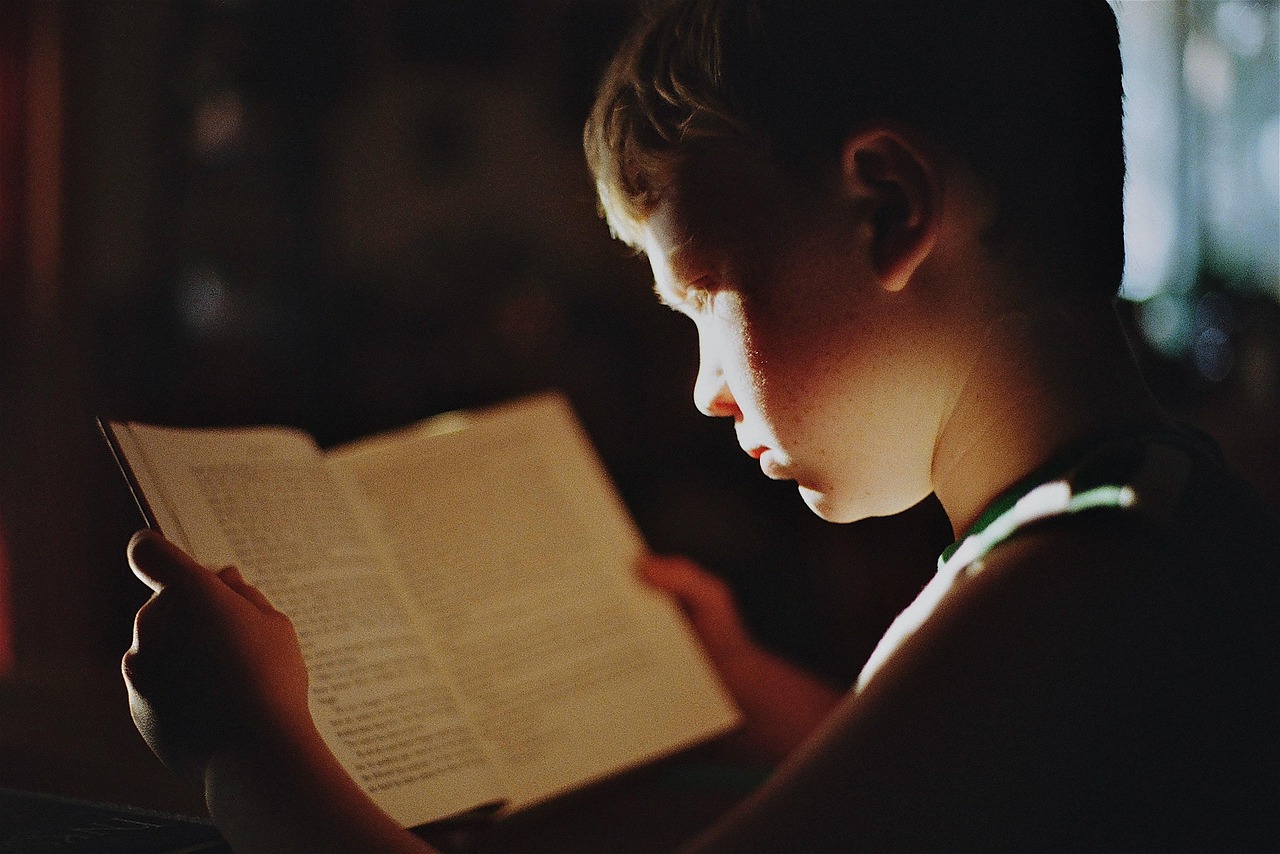

- Note: Many who went through this declutter rediscovered their love of reading actual books. The very act of reading helps improve your ability to focus, creating a virtuous cycle.

- Selectively reintroduce technologies into your life after one month, but only the ones you deeply value.

- Note: It can be hard to know what you truly value until you give yourself some time and space to explore other possibilities.

Carefully Structure Your Time

Another angle to attack the focus problem is how you manage your time. Several of the suggestions here come from Newport.

Try multi-scale planning. This involves planning for various time scales in your life, such as annual, quarterly, and monthly intervals. You can then drill down into weekly and daily plans.

This approach can feel overly structured to some people. However, having the right amount of constraints in your time can paradoxically give you the sense that you have enough of it. Consequently, it becomes easier to give sustained attention to the more valuable things in life. On a daily planning level, using time blocks on your calendar can be a great way to achieve this.

While I can’t foresee everything that will happen over a week, part of my weekly planning involves setting up tentative time blocks for each day in the week ahead. If a new obligation arises during a workday, and it inevitably will, I can make a conscious decision on where to allocate the time for that task. I can then set proper expectations for those who depend on me to complete that task.

Another benefit of incorporating structure into your week is that it can give you the confidence to say no to, or postpone, incoming requests. While it may not always work, especially with superiors, you can cite the obligations on your plate. It may feel risky, and it can be difficult initially. However, a great way to regain your focus is to assert your ability to say no.

Have a shutdown ritual at the end of your workday. It’s important to remember that high levels of focus and attention are intended for a limited number of hours each day and for specific times when your energy is at its peak.

An extension of this is to set a specific time of day when you are truly done with work. Before that time arrives, you can create a ritual that allows you to mentally disconnect. It can be as simple as reviewing your tasks and obligations for the next day or doing a “final” email check. Newport even recommends a certain mantra you say to yourself at the end of the workday. I believe the one he uses is “Shutdown Complete.”

I know people who take pride in working every day, but I recommend taking at least one full day off each week. This may seem like a strange suggestion. Don’t most of us already have two days off, also known as the weekend? I’m not so sure anymore. It feels as though we’re working all the time, especially since the pandemic

From Hari’s book, he recounts the story of a business owner in New Zealand who conducted a two-month experiment to determine whether a four-day workweek was feasible without harming the bottom line. It was indeed feasible, and it became a permanent way of conducting business.

The new time constraint encouraged a greater focus and creativity that they might not have otherwise felt inclined to cultivate. I covered a similar aspect of this in an earlier blog, Increase Your Productivity by Reversing Parkinson’s Law.

Furthermore, the employees at this company were happier. They could spend more time with their families and children and be more present for them. They felt rejuvenated when they returned to work after each “long” weekend.

In the end, attention and focus are not just metrics to maximize; instead, they are fundamental parts of what makes us feel more fulfilled. We know enough to pay attention to our diets, exercise, and sleep. Notably, all of these contribute to improved focus as well. Let’s devote as much attention to our focus muscles and prevent them from atrophying.

If you have comments or questions on this piece, please drop me a line at: [email protected]

References

- https://stolenfocusbook.com/

- https://thesocialdilemma.com/

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/40672036-digital-minimalism

- https://krishnawealth.com/increase-your-productivity-by-reversing-parkinsons-law/

The information on this site is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Krishna Wealth Planning LLC (referred to as “KWP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

KWP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. None of the information provided on this website is intended as investment, tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall KWP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the materials in this site, even if KWP or a KWP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages.

In no event shall KWP have any liability to you for damages, losses, and causes of action for accessing this site. Information on this website should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.