7-Minute Read

“Free lunches don’t come cheap.”

– Charles Petzoid (American Programmer)

I’ve been having more conversations lately with families concerned about protecting their investments against downside risk. That’s understandable. We’re still in the thick of a devasting pandemic. Meanwhile, plenty of uncertainty remains in our political and natural environments.

There are providers of financial products eager to take advantage of your fears by marketing solutions that promise to eliminate the downside risk of investing. On top of that, they suggest you can participate in the upside benefits too. Is this too good to be true? This piece takes a closer at one such product, the equity indexed annuity, with the idea of preparing you to see past the allure.

What is an Equity Indexed Annuity?

An equity indexed annuity (herein let’s call it EIA for short) is simply a contract with an insurance company that has an investment component. The return you receive is tied to the performance of an equity index, such as the S&P 500. EIAs typically have a minimum promised return, meaning you should be contractually guaranteed to at least get that “floor” return. On typically an annual basis, if there is a positive return of the equity index, your account gets credited with a portion of that return.

Note: The rest of this piece picks on the EIA. But let’s clarify that there are different kinds of annuities in the marketplace, and some can be suitable based on your retirement income planning goals. Single premium immediate annuities (SPIAs) and Deferred Income Annuities (DIAs) are two such products that can potentially help you manage longevity risk (the risk of living too long). As a fee-only advisory firm, Krishna Wealth Planning does not sell (or receive compensation for recommending) insurance products.

A Twenty-Year Comparison of the EIA with a Conventional Stock/Bond Portfolio

What we’ll do to learn more is look back at the most recently completed two-decade period from the start of 2000 to end of 2019. Care should be taken to avoid “cherry picking” when looking back at any period and comparing investment strategies. But for a few reasons to come, the following comparison should allow us to draw some reasonable conclusions. Let’s first look at a few key assumptions before revealing the results.

Stock and Bond Portfolio Assumptions

We will start with a “vanilla” stock and bond portfolio that might be used by a conservative investor. For this example, let’s use two mutual funds from Vanguard that provide broad exposure to the US markets at a low cost. At the time of this writing, these two funds are available to any investor who can meet a minimum investment of $3,000 per fund.

- Vanguard 500 Index Investor (Ticker VFINX) for US Stock Market Exposure (20% Weighting)

- Vanguard Intermediate Term Treasury (Ticker VFITX) for US Government Bond Market Exposure (80% weighting)

For risk management, assume that these funds are rebalanced annually to an allocation of 20% stocks and 80% bonds. Let’s further assume the portfolio is managed by an advisory firm for a 1% annual fee. Additional costs like transaction fees and taxes are not factored into this analysis.

EIA Assumptions

For comparison, let’s assume an EIA contract using a typical S&P 500 crediting strategy. Other benchmark indices are available and can be used, but they might not be as directly comparable to the stock/bond portfolio just described.

EIAs typically offer a variety of different crediting strategies to choose from. They may go by names like monthly or annual point to point cap. Or they may use a flat “participation rate.” Suppose you had a contract with a 25% participation rate. If the S&P 500 benchmark price (not including dividends) increased by 16% over the past year, you would get 4% credited to your account.

For this example, I picked an insurance company (not to be named here) that had a variety of crediting strategies available based on monthly S&P 500 closing prices. Among them, I choose the strategy that yielded the highest return over this 20-year period, which coincidentally was an annual “point to point” with a 25% participation rate. If there was ever a year with a decline in the S&P 500 price, nothing would be credited or debited from the account balance.

If you’re considering an EIA, take a close look at the contract’s language and understand how the crediting formulas work. For example, some contracts may have participation rates that vary over time. Some may have higher participation rates, but other limitations are applied first. It’s important to understand how your contract will be perform under different types of market environments.

Finally, I assume NO asset-based fees (or front-end commissions) are paid to the insurance company providing the EIA. This may be unrealistic for many products in the marketplace, especially if you have any type of “riders”, or additional benefits added to your contract. My goal here is to give the EIA the benefit of the doubt.

The Results

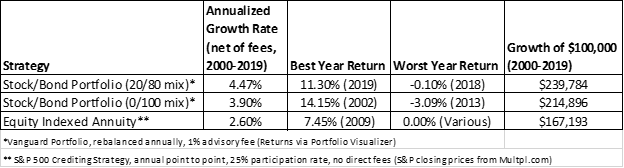

- From 2000 to 2019, the 20/80 stock bond portfolio had a compound annual growth rate of 4.47%. Remember this is after a 1% annual advisory fee is applied. This turned a $100,000 investment into $239,784. The best year this portfolio experienced was 11.30% (2019) and the worst was -0.10% (2018). This result is courtesy of Portfolio Visualizer.

- Over the same period, the EIA had a compound annual growth rate of 2.60%. This turned a $100,000 investment into $167,193. The best year this portfolio experienced was 7.45% (2009) and the worst was 0% (no credit was applied in 7 different years). If you would like to see the calculations used to arrive at these figures, please email me at [email protected]

So, the stock/bond portfolio in this example ended up with a portfolio around 43% higher ($72,591 dollar difference). By many standards, a 20/80 portfolio would be considered very conservative, and it proved to be at least over this back tested period. Higher returns, but with more volatility, could have been achieved with a higher stock allocation.

The EIA result was poor by almost any standard you can apply. Note that inflation itself, as measured by CPI, was around 2.1% over this period. This means you would have barely increased your purchasing power at the end of twenty years. This EIA would have needed to offer a pure participation rate of around 43% (without any other limitations) just to match the stock/bond portfolio.

Even if you chose to invest 100% in the noted treasury bond fund (no stocks at all), you would have netted a 3.90% return with a final account balance of $214,896. Here are the results in table form below.

Are These Results Surprising?

To understand why these results should not be surprising, it may help to look at the way insurance companies commonly choose to build their EIAs. Here are two examples.

Inside an EIA – Example #1

For some EIAs, the insurance company is NOT absorbing the risk on your behalf the way you think they might be. With money you give them, they could invest it in relatively safe fixed income securities (think treasury or investment grade corporate bonds). They’ll use the interest income produced from the bonds to cover their overhead costs and ensure they reach a certain profit margin.

For the money that remains, they will buy derivatives (think stock options) on the appropriate equity index. If those derivatives pay off, they can credit their investors accounts. If the derivatives expire worthless, they simply don’t credit the account. Either way, they’re not really absorbing a risk you’re not somehow willing to take.

In a low interest rate environment (like we’re in today), insurance companies have less money available to buy derivatives. In turn, they must offer a lower effective participation rate to their EIA investors.

Inside an EIA – Example #2

My friend and colleague, Daniel Yerger at My Wealth Planners, recently pointed out to me another way some insurance companies build EIAs. They may or may not use derivatives. But what they do is directly purchase investments representing the underlying index, like the S&P 500, and your return is tied to the face value of the index. They can make claims such as: “This is a no fee product that invests in XYZ index. If the market goes down, it doesn’t lose value. If the market goes up, it goes up.”

This is misleading for a couple of reasons. First, the insurance company will keep all the dividends and interest from the index, which when issued directly lowers the face value of the index. This is just how market pricing works. Equity is converted into cash and paid out to shareholders.

Second, they apply a participation rate or cap, as discussed earlier. These can severely restrict your returns. Are they shielding you from losses? Sure, but it’s at the cost of taking a large portion of your annual returns as a buffer!

Are the insurance companies at least absorbing your risk in this second example? Again, not as much as you might think. They know that while it’s very possible for some severe down years in the market to occur, it’s very unlikely they will not achieve a positive return over a long period like ten years.

Also, most insurance companies will put in place long surrender periods. If you terminate your contract too early, surrender charges will apply and they can return your invested capital (less surrender charges) and be in no worse position on their books.

What Should We Expect Going Forward?

With bond income yields as low as they are today, a fair argument could be made that you cannot expect the same results described earlier to repeat in the next twenty years for a portfolio that is heavily weighted towards bonds. Could that fact or other circumstances make an EIA a more viable solution going forward?

While we cannot know definitively, remember that insurance companies are subject to the same capital market environments as any other investors and firms. It’s true they may have some trading efficiencies over a smaller investor due to their size and scale, but their investment strategies can be broadly replicated by you as an individual investor if you were so inclined.

Let’s end by noting the classic line that there is no free lunch in investing. If you have comments or questions on this piece, please drop me a line at: [email protected]

References

- https://krishnawealth.com/the-sp-500-can-the-familiar-be-unknowable/

- https://www.napfa.org/financial-planning/what-is-fee-only-advising

- https://www.multpl.com/s-p-500-historical-prices/table/by-month

- https://www.portfoliovisualizer.com/

- https://www.mywealthplanners.com/daniel-yerger-mba-cfp-aif-cdfa/

The information on this site is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Krishna Wealth Planning LLC (referred to as “KWP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

KWP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. None of the information provided on this website is intended as investment, tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall KWP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the materials in this site, even if KWP or a KWP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages.

In no event shall KWP have any liability to you for damages, losses, and causes of action for accessing this site. Information on this website should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.