11-Minute Read

“Computers are useless. They can only give you answers.” – Pablo Picasso

A common question asked of financial advisors is a variation this: “How much money must I accumulate to retire comfortably?” It is fair question, but a surprisingly profound one too. The answer people expect to hear is a dollar figure also known as the “retirement number.” While useful to know this, it can be powerful to complement it with a different type of number. Here we will call it the retirement success rate. This piece describes and compares the two approaches with the ultimate hope that quantifying your target, regardless of method, can be a helpful step towards reaching your retirement goals.

Method #1 – Your Retirement Number as a Dollar Figure

It is quite a thing to know if you’re on track for retirement. But some people just want to know a simple dollar amount they need to accumulate to retirement comfortably. It’s a fair but loaded question as we’ll soon see why.

If advisors in the not too distant past were asked this question by a stranger on the spot, they would probably take some time, ask a few questions and run through the numbers with a paper, pencil and maybe a calculator. This would close to a “back of the envelope” approach. It’s not fundamentally different answering the question today. Maybe it’s done paperless instead with a smart phone app or on a tablet computer with a spreadsheet. Method aside, it can help to know (or be refreshed) on the key assumptions that go into generating the retirement number.

Retirement Number Assumptions

- Years until retirement – this is the number of years from now until your desired

- Years expected in retirement – this is your life expectancy minus your desired retirement age. This is often, but not always, the number of years you expect to make withdrawals from your portfolio. While your own lifestyle and family health history are key factors, a simple life expectancy calculator can be found on the Social Security website and used as a starting point.

- Income goal from portfolio – this approximates how much you wish to withdraw from your portfolio each month in retirement in today’s dollars. This can be tricky, but here are a couple of suggestions to help you arrive at a reasonable estimate:

- Start with your current household wage/business income and take some percentage of that (e.g. 70% to 80%). Roger Young recently explained some of the considerations households face when finding their own income replacement

- Start with your current level of living expenses (including taxes, excluding savings). Then adjust from there. Here are a couple possible adjustments:

- Reduce for expected for outside income sources such as Social Security, Pensions and Annuities.

- Increase for any expected higher expenses in retirement. This can include travel, healthcare, long-term care insurance premiums, special goals, etc.

- Inflation Rate – this helps quantify how your income need will grow over time as cost of living rises. In today’s environment, you might use 2% or 3%.

- Rate of Return Expectation – how much do you expect your portfolio to grow on average every year up to and during retirement? This alone is a topic worthy of much separate discussion. But if you were reasonably confident your portfolio could generate a return (after inflation and costs) of 4%, you could add that to the preceding inflation rate and use 6 or 7% as your return expectation here.

- Capitalization Rate – there are different definitions of this fancy word depending on how it’s applied. Based on the assumptions above, a percentage can be derived that effectively becomes a multiple of the income goal. If 4.0% were the “cap rate” you chose, this means you would want 25 times (1 divided by 0.04) your annualized, inflation-adjusted income goal as your target portfolio size (a.k.a. retirement number)

- Starting Portfolio Size – this is not technically needed for the retirement number, but it can help put proper perspective around the number once you have it. Here you add up the current market value of all your liquid investable assets. This includes taxable accounts, IRAs, qualified plans, etc. You might choose to include current cash account balances. You might also want to include an approximate value of rental real estate and other illiquid business interests (net of liabilities). Typically, you’re excluding the value of your personal residence and personal property. You would also exclude annuities if you’ve accounted for them in the income estimate above.

- Bridge Portfolio Needs – while also not an absolute necessity, it’s often desirable to include this nuance. Say you intend to retire at age 62, but you don’t intend to claim Social Security benefits until age 67. You might like to carve out your own “bridge” portfolio to replicate that Social Security income for five years. For more on this so-called bridge planning, you may refer to this piece by retirement thought leader, Jonathan Guyton.

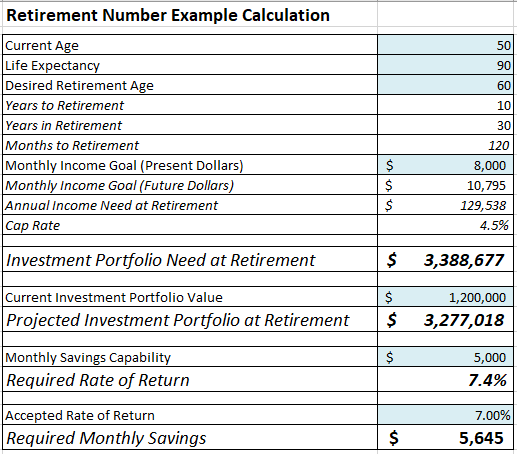

Retirement Number Example

Once you feel you’ve identified reasonable assumptions above, the next step is to run them through some time value of money formulas to estimate a retirement number. It may help to look at a brief example without getting deep into the actual formulas.

Suppose a married couple, where both spouses are 50 years old and they want to retire in ten years at age 60. They’d like to plan for 30 years of retirement income. Ideally, their future portfolio could sustain monthly spending of $8,000 in today’s dollars. They would also like to save enough for a seven-year “bridge” portfolio to cover $4,500 per month in combined Social Security benefits that they intend to start collecting at age 67.

When I run this scenario through a few calculations, I estimate this couple will need to accumulate almost $3.4 Million in ten years. This becomes their initial retirement number.

A second question then usually arises. Is this couple on track to reach their goals? Let’s say they currently have a portfolio worth $1.2 Million. If they were willing (and capable) of saving $5,000 per month from now until retirement and earn a 7% return on their invested capital along the way, I’d estimate they would be pretty close to the target and end up with a little under $3.3 Million at the start of their desired retirement. The picture below captures the essence of this scenario.

If that savings rate of $5,000 per month were not possible, we could look at alternative solutions like working longer or trying to generate (with no guarantees) a higher return on the investments. The main idea is that keep iterating until we find a retirement number and savings strategy that seems reasonable.

Benefits of the Retirement Number Approach

- Simplicity – You make a few assumptions, run them through a few formulas and end up with a nice round number. Yes, it takes some time to gather the right assumptions. But overall, it’s a relatively simple and fast approach.

- Motivational – Having a concrete number in mind can give you a goal to work towards. It can help motivate you to pick a certain monthly savings target, implement it and possibly even stick with it. Behavioral economists might suggest there’s a lot more that goes into promoting good saving behavior, but simply having a goal in mind isn’t a bad start.

Problems with the Retirement Number Approach

- Life is Dynamic, Not Static – The variables that drive the retirement number change based on how your life (and lifestyle) evolves over time. Depending on the magnitude of the changes, your number can change too. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. But a moving target may not be the most useful target. That said, it is simple to re-compute when needed.

- Market and Tax Distortions – Based on the nature of investment markets, a dollar amount can mean different things at different points in the economic cycle. Even if you reached retirement number target, but investment valuations were rich at that time, this might not be better than having missed the target but doing so in an environment where valuations are lower. This is another way of saying that current valuations impact future long-term expected returns. Also, based on the type of tax vehicles you’re investing in, a dollar amount may mean different things too! But this can be mitigated to some extent by adding in a conservative estimate of taxes in the income goal need estimate.

Method #2 – Your Retirement Number as a Success Rate

In this life, we have one shot at getting things right. But imagine if you could live your life in a thousand or more parallel universes. In each universe you have a different (and sometimes wildly different) experience. Some of those critical variables mentioned earlier (e.g. investment returns, inflation) also take their own random path in each universe.

Why would this science fiction-like thinking be helpful? We simply can’t know for sure how our lives or the world around us will change in the decades ahead. If we could see many realistic possibilities on how things could possibly play out, an improved way of knowing if our financial plan is on track is if a healthy majority of these hypothetical lives has a successful outcome.

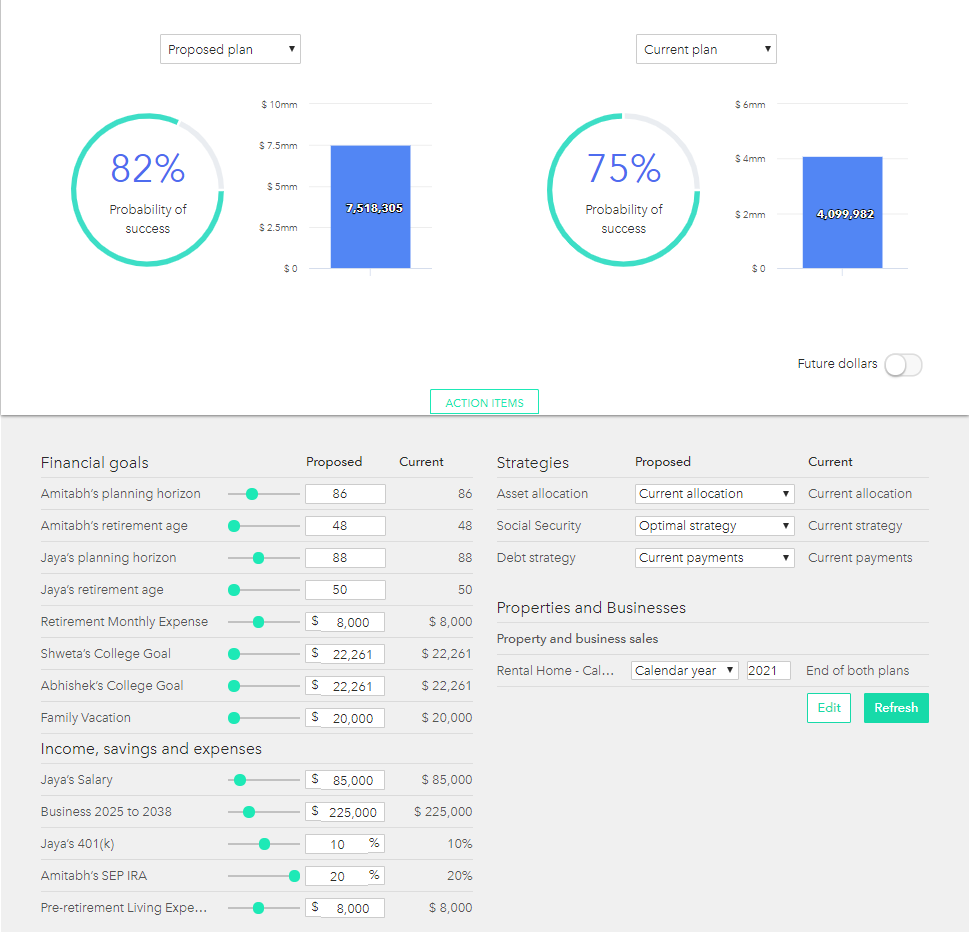

The good news is our technology today allows us to stress test our financial plans in this way. Most advisors call them Monte Carlo simulations. With a Monte Carlo stress test, the primary output is a success rate (or probability of success percentage) that ranges from 0% to 100%. Success in this context typically means being able to meet your cash flow goals every year for the rest of your life. The higher the number of “universes” where that is true, the higher your success rate.

The next question might be should you aim for a 100% success rate? My take is probably not. When building retirement plans for clients, I’m often targeting a success rate of “only” 75% to 85%. This tends to be in the sweet spot of living the best life we can now while building protection for an unknown future. We should know that having some implied “failure rate” here doesn’t mean the same thing as failing a reliability test on a physical product. The opposite of success isn’t really failure anyway. It’s more about acknowledging the fact we may need to make some mid-course corrections or adopt different planning strategies along the way. Planning expert Michael Kitces calls it a probability of “adjustment”.

Benefits of the Retirement Success Rate Approach

- Accuracy – Monte Carlo engines can vary in design, but the more it is driven by a detailed financial plan, the more accuracy we can expect. The assumptions used in the first retirement number method are just a starting point. In a financial plan, we can get much more specific with our year-to-year assumptions that more accurately reflect income, expenses, savings and taxes. These again must all be approximated in the dollar method. Today’s technology tools are also capable of looking at the underlying investment holdings and generating custom risk/return assumptions.

- Flexibility (and Fun) – In the past, assume a client asked an advisor what happens IF I retire two years earlier or spend 10% more. Unless that advisor had exceptionally quick computation skills, it probably required going back and revising the plan and making sure the results still met a certain margin of safety. Now an advisor can let the client move their own dials and see the new results within seconds. The planning software, with integrated Monte Carlo, has continued to improve over the years. It is now a flexible, interactive tool I personally use with clients. In some ways, I don’t have to tell anyone what they should do or not do. They can see it for themselves. I can just be a guide to help them navigate the tradeoffs between competing financial goals. I’ve found it just makes the financial planning experience more fun.

A sample Monte Carlo snapshot for a fictional client is shown below from the software my firm currently uses, RightCapital.

Problems with the Retirement Success Rate Approach

- Costs (if outsourced) – Free tools available on your computer or downloadable from the internet may not be capable of generating the results you need that are both accurate and actionable. Hiring a financial advisor may be necessary to build and maintain a Monte Carlo-based plan. They also have the skills and insights to properly set up your plan in a way that makes sense of the outputs you see. I’m probably biased to think that is money worth spending, but it is a cost to take into account.

- Time (if DIY) – To get a Monte Carlo simulation ready for a client, I personally spend a good deal of time upfront getting organized and going through a proper discovery process. Even if you’re a “do it yourselfer”, that could present some challenges. I work with several clients with a technology background who have the skill set to build their own Monte Carlo simulators. But I have not (yet) met anyone that had the both the time and interest to do this type of exercise on their own.

Ultimately Just Guideposts for Your Journey

In the end, the two approaches described aren’t necessarily competing. They can be complimentary and serve different purposes. These ultimately are just pieces of a thoughtful financial plan. Think of these numbers as guideposts on your journey. Either number is effective if it can help drive better financial behavior and decision making.

If you have comments or questions on this piece, or if you would like a complimentary spreadsheet template for generating your own retirement number, please drop me a line at: [email protected]

References

- https://www.ssa.gov/oact/population/longevity.html

- https://www.kiplinger.com/article/retirement/T047-C032-S014-how-to-estimate-income-you-ll-need-in-retirement.html

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/timevalueofmoney.asp

- https://www.onefpa.org/journal/Pages/JUN15-Bridges-to-Social-Security.aspx

- https://www.kitces.com/blog/renaming-the-outcomes-of-a-monte-carlo-retirement-projection/

The information on this site is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Krishna Wealth Planning LLC (referred to as “KWP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

KWP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. None of the information provided on this website is intended as investment, tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall KWP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the materials in this site, even if KWP or a KWP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages.

In no event shall KWP have any liability to you for damages, losses, and causes of action for accessing this site. Information on this website should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.