7.5-Minute Read

“In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

-Benjamin Graham

In recent years, value investing has had its challenges. What does it mean to be a value investor? This piece attempts to answer that while going a level deeper into the investment philosophy and process used at Krishna Wealth Planning. While the question of whether value investors be rewarded again is hard to answer definitively, there are compelling arguments in its favor when we examine the theory and apply some historical perspective.

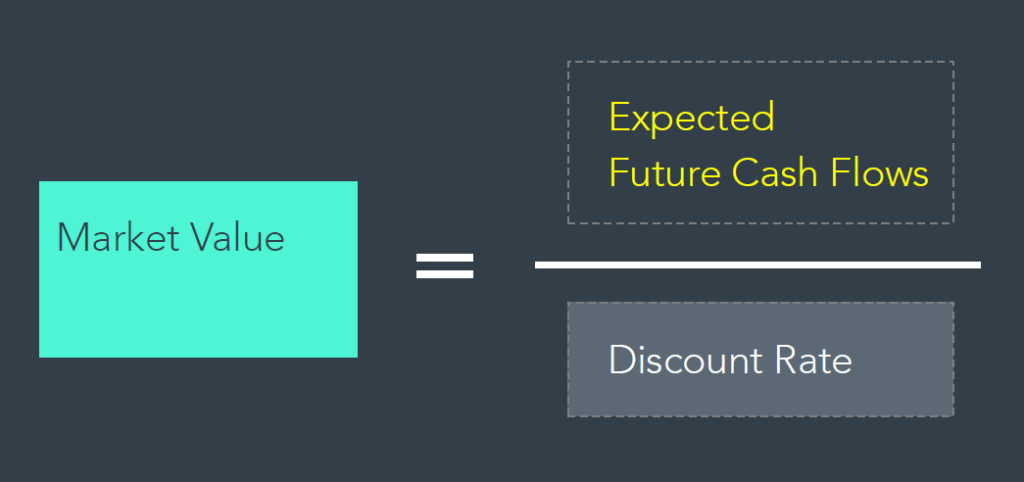

The Valuation Equation

Let’s start with the essential point of this piece: Expected returns are driven by prices investors pay and the cash flows they expect to receive. I suppose you could stop reading right now. It might also help to see how that point is captured in the valuation equation below. I generally try to limit my use of equations in blog pieces, but this one is worth a moment of inspection.

- Market Value – The current price of a company’s stock.

- Expected Future Cash Flows – There are different metrics to quantify this, but let’s call this a company’s future profitability.

- Discount Rate – This is simply the link between a company’s future profitability and its current price. This resulting rate, often expressed as a percentage, is same thing as the company’s expected return.

If we were all rational investors (ok, big assumption), we would attempt to maximize our expected returns (discount rate), at least to the extent we could handle the risk of an investment. A couple of examples may help.

- Take two companies A and B. If both companies had the same expected future cash flows, but A is trading at a lower price than B, the valuation equation shows (all else equal) that A must have a higher expected return than B. This point is at the heart of the value premium which will be discussed next.

- There’s another way to interpret this equation. Not every company has the same level of expected future cash flows. If company A and B were trading at the same price, but B had a higher expected cash flow than A, then company B would instead have the higher expected return.

What is the Value Premium?

The value premium is simply the observed tendency for relatively cheap assets to outperform relatively expensive ones. It’s a rather simple and intuitive concept yet many investors have a hard time grasping it. Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett’s mentor, understood the concept well before most practitioners and academic researchers.

You might have heard of stocks being classified as “value” and “growth”. The value stocks are those relatively inexpensive ones, and growth stocks are the relatively expensive ones. Technically the “premium” is computed by taking the average annual return of value stocks and subtracting the average annual return of growth stocks. The return difference is the value premium, and we’ll quantify this shortly.

Criteria for a Premium

With the vast computing power available today, researchers (and even ordinary individuals) have access to large financial data sets and the statistical tools to make inferences from that data. The value premium is focus of this piece, but it’s not the only premium identified in the investment research. When looking at any potential premium, care must be taken not to infer the wrong the conclusions from data.

A premium should meet several criteria to be considered viable and thus likely to materialize in the future. Andrew Berkin and Larry Swedroe, prominent investment researchers, give us a helpful starting point for that criteria as follows, which is taken from their book on Factor Investing.

- Persistent – It holds across long periods of time and different economic regimes.

- Pervasive – It holds across different countries, regions, sectors and even asset classes.

- Robust – It holds for various definitions. For example, the value premium can be defined by measuring by a stock’s price relative to book value, earnings, cash flow or sales.

- Investable – It holds up not just on paper, but also after considering implementation issues such as trading costs.

- Intuitive – There are logical risk-based or behavioral-based explanations for the premium and why it should continue to exist.

How Has the Value Premium Performed Historically?

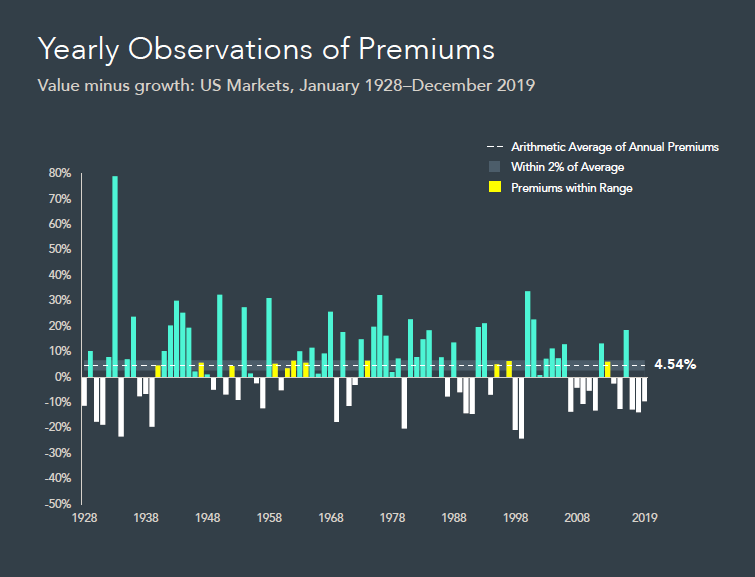

Ok, let’s put some numbers behind this. Based on research from Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA)1, the average annual value premium in the US from 1928 to 2019 was 4.54%. Remember this is not the absolute return of value stocks. Rather it’s the average difference in returns between value and growth stocks. It turns out to be a meaningful difference.

But on a year-to-year basis (as shown in the figure above), the realized value premium can be quite volatile and look much different than the long-term average. Because yearly results can be noisy, it could help to look at 10-year rolling periods. The same research shows that the US value premium has been positive 83 percent of the time since 1937.

The flip side is that 17 percent of the time, the value premium has been negative. In other words, you would have (at least in theory) earned higher returns in growth stocks. Interestingly, some of the worst underperformance of the value premium has occurred within this past decade. That’s why it’s timely to ask if value investors will be rewarded again!

- In the last decade (2010 – 2019), the value premium was negative in the majority of the markets around the world. The global average premium was negative 3.8% and the US was close to that at negative 4.0%.

- The previous decade to that (2000-2009), the value premium was positive in most countries around the world. The global average was positive 10.8% and the US again was close to that at positive 10.6%.

Remember from the previous section that to be considered a viable premium, it also needs to be pervasive across different countries. That has been the case for the value premium. According to additional research by DFA2, the value premium has been positive in the Non-US Developed markets going back to 1975 and in the Emerging Markets going back to 1989.

Beware of Chasing or Avoiding Premiums

History has shown us that premiums can materialize quickly. As noted earlier, we’re currently in a long period where growth stocks have outperformed value stocks. But this is not new. The same occurred in the late 1990s during what we may remember as the dot.com bubble. During that period of around 2000-2001, the pendulum swung rapidly, and we observed a sizeable value premium for the subsequent decade.

This is not a prediction that the same is going to happen soon for the value premium. It’s more about setting the right expectations. There can be a substantial opportunity cost to staying away from underperforming premiums. Historical valuations for growth stocks is high. We can always ask if something is different this time? Time will tell, but there’s no reliable way to time your exposure to this or any premium. Capturing a premium is like an airline asking you to stay in your seat but not telling you exactly when the plane is going to take off. To get to your destination, you must stay in your seat.

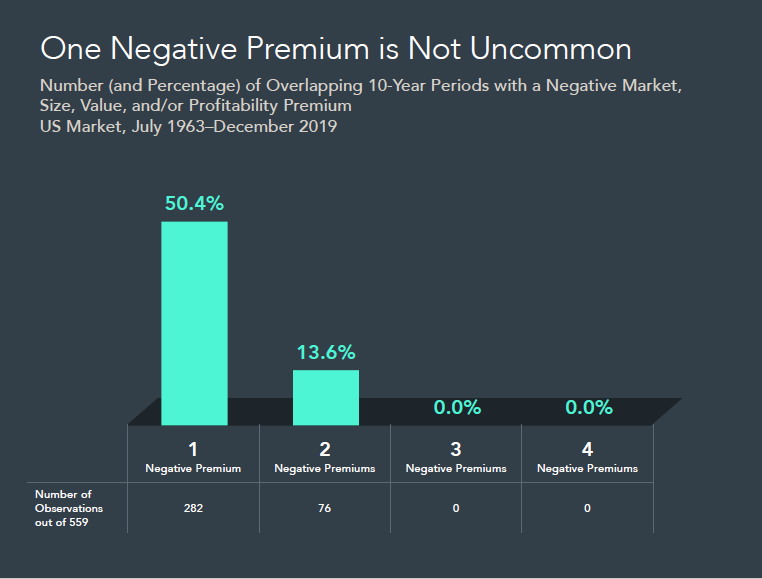

So, if chasing (or avoiding) the value premium has its flaws, what about combining it with other premiums? In another interesting study by DFA2, looking at US data going back to 1963, they used four of the major equity market premiums (value, market, size, and profitability). Then they looked at overlapping 10-year periods resulting in 559 observations. The results are in the figure below.

50.4% the time (282 observations), there was one negative premium of the four used. A coin flip, right? Then 13.6% of the time (76 observations) there were two negative premiums. Interestingly, there were zero observations of 3 or 4 negative premiums. This doesn’t mean that it’s impossible for that to happen in the future. The key point is that having exposure to multiple premiums helps mitigate the risk of any one premium underperforming.

Focus on What You Can Control

Equity premiums, including the value premium, are volatile. They can go through long periods of underperformance. That might sound scary on the surface, but it may be just what we need as investors. Think of it this way: If there was no volatility, there would be no premiums to capture. To keep this piece from getting too long, we won’t get into how to capture premiums in your own investment strategy, but that’s an excellent next question to explore!

As investors, we should focus on what we can control in our investment plans. Among other things, this includes long-term focus, broad diversification, integrating multiple premiums and efficient implementation. This doesn’t necessarily make investing any easier during stressful times. But such discipline can improve your chances of having a successful investment experience.

If you have comments or questions on this piece, please drop me a line at: [email protected]

References

- “A Perspective on the Value Premium” – Dimensional Fund Advisors, Kevin Green, PhD 2020-02-19

- “Why Value” – Dimensional Fund Advisors, Gerard O’Reilly, PhD 2020-05-21

The information on this site is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Krishna Wealth Planning LLC (referred to as “KWP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

KWP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. None of the information provided on this website is intended as investment, tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall KWP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the materials in this site, even if KWP or a KWP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages.

In no event shall KWP have any liability to you for damages, losses, and causes of action for accessing this site. Information on this website should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.